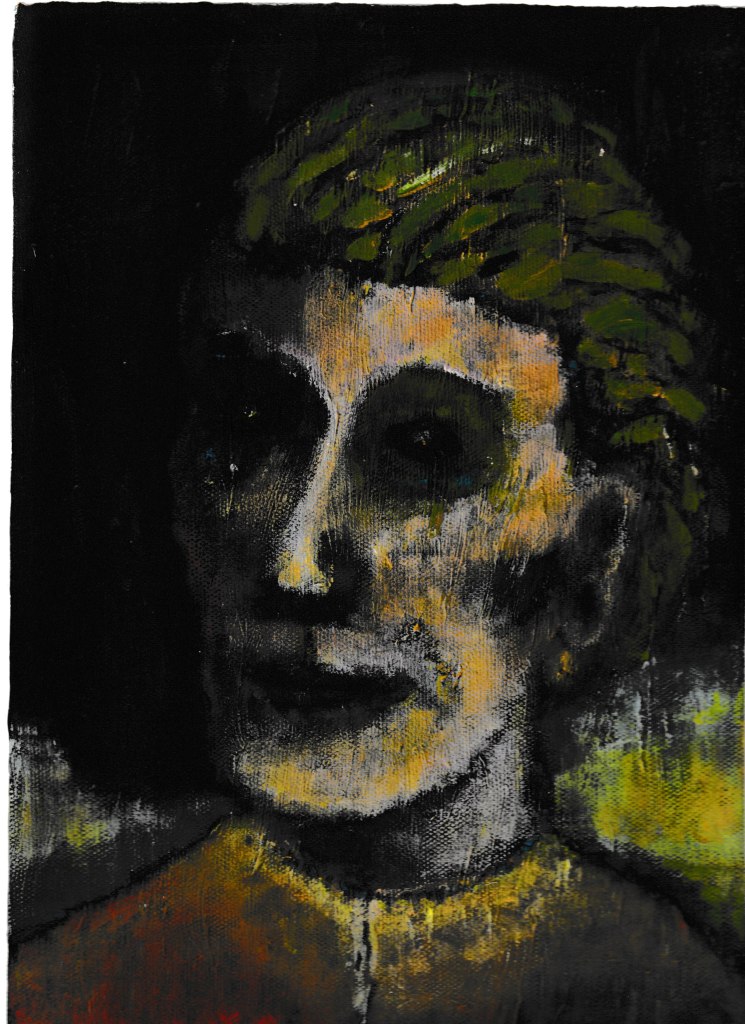

[I don’t claim to be any kind of painter, but do it, for good or bad, from time to time. The painting of a face from a dream is at the foot of the piece of stream writing. Must writing make sense to the writer? Not at all. Life doesn’t make sense, after all. Writer and reader may understand the sense of it, make sense of images here and there, find words that move or shock, echo or reflect. It’s all I can do. ]

The ghost returns from the end of the mind.

We are not welcome in his world.

All the hurt returns from the shadowy alleyways

of the also-rans, the never-could-have-beens.

I find a letter I didn’t post to you from the red hills of the next world.

Idealistic, almost juvenile, but how neat my hand-writing was.

There are wildernesses (of the heart, I hear you say – no, no, no!)

Wildernesses into which you can only walk.

Forget flying, even if you could afford it.

The storms, you see.

That summer when we visited Huish Champflower, do you remember?

In search of your ancestors.

Two people were changing the flowers in the church, sweeping up.

Pleased to see us, they showed us a map of the graveyard,

which told us who lies where there are no stones.

The wildfires are spreading like wars. We need to get out.

Airports have closed.

People walk the roads with suitcases.

We get into the car and drive into history,

using a map of Europe from before the meteor.

We give the kids an I-Spy Book of Dinosaurs

to keep them quiet for an hour or so.

They look hopefully out of the windows.

You’re wearing that light yellow shirt,

the top two buttons undone because of the heat.

Your silver crucifix shines as the sun diffuses

through the windscreen dirty with bugs.

All the hurt you hand out stays with you.

The earth is just another organism.

Its capacity for self-regulation can go only so far.

Words, grand gestures.

It’s too late, baby, it’s too late.

But we really did try to make it.

Did we? Try, I mean?

The poor house is still standing

across the track from the well-kept church

but nobody can afford to run it any more.

In one country the executions go on.

In another they guess how many children died when the shell hit the hospital.

The old man selling trinkets at the motorway service station says to himself

I’d have done anything for her. I should find her while there’s time

but I doubt we’d recognise each other, or perhaps ourselves.

My phone dings. It’s the phone company telling me

my phone usage has increased over the last week

to an average of forty-four minutes a day.

Absurd. Can’t be right. I need to reduce that.

On the radio news, they say the motorway is blocked

by a sleeping, possibly flatulent brontosaurus.

The public are warned not to approach it.

Diversions are in place. Delays are inevitable.

Surely, they can open one lane, says our eldest.

I want to see it and cross it off in my book.

We drift along, year after year, life after life.

When all the masks you’ve ever worn peel off, drop off, fall off,

go on, drive north. Tell no one. Don’t think about destinations.

And if you must speak, be slow about it.

And speak only when the wind is against you.

Be what they always told you that you would be:

Obscure, hidden, restrained.

We pass through a town.

You say I’m not the one you’re looking for.

The town is very yellow.

(All day and the next but not the one after that.)

In the park in the 1960s the ice-cream seller asks

Wafer or cornet?

It’s your choice. You kept all of his letters for years

until one day irrelevance slapped you hard.

You took them all out of the bundle

(kept the string, string is always useful)

threw them into the plastic recycling bin

with the blue plastic lid.

Blue for recycling, black for not recycling, green for garden waste.

I don’t mind being objectified, misunderstood.

You thought you knew me?

Bones always answer back.

A scar edges further across paper skin.

Cheeks are hollowing out.

Young people are removed from their homes by the busload.

They don’t know where they’re going.

They will forget where they’ve been.

In a suburban garden – over there, do you see, the house

with the naked woman washing the windows –

a sparrow hawk just swooped on a blackbird.

It’s eating it in full view of the children,

who, as it happens, don’t really mind.

Are we going to the seaside? asks the youngest

from her car seat. Yes, you tell her, we’re going

where the water is so clear you can see

the sea-bed (where a woman’s

wedding ring – and a silver tooth – lie

forgotten in the sand.) Think it, I think,

but don’t say it aloud.

That was then, this is tomorrow. And we did go clear.

Of ourselves, of each other, the children grew up and away.

I hear you run creative writing classes for the elderly.

I know your other husband died young.

Ah yes, I remember writing to say I hoped

you’d enjoyed the exhibition of ice sculptures.

And, in fairness, you did tell me

profit would destroy us piece by piece.

You did say it was already too late

for the dawning of the age of Aquarius.

Oh, cut out the self-pity.

Here you are then.

You can see the sea now.

The key to the cottage

should be in the box

by the door.

Have you remembered

the code?

The door creaks, just

as it always did.

Here’s the ghost.

Still got that weird smile.

We’re not welcome.

Never were.